Date of publication: January, 17, 2022

Русская версия: Как власти используют камеры и распознавание лиц против протестующих

Introduction

«On the morning of Sunday [April 25, 2021], I woke up to the fact that someone was knocking very insistently on my dorm room, ” says Artem Pugachev, a student. «My neighbor opened the door, and then the police officers entered unceremoniously. In a rather aggressive form, they told me that it was time to get ready ― that we will go to a police station. They did not respond to my demands to clarify on what basis. In a semi-compulsory manner, they escorted me to the car and took me to the station.»

At the station, the police issued a detention. Pugachev spent two days in detention, and then he was found guilty of repeated violation of the procedure for holding a public event (Part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences) and was sentenced to ten days of arrest. The student was charged with participating in a rally in support of Alexei Navalny, held in Moscow on April 21.

After the April rally, many wondered: why were participants detained in large numbers only in some cities? Unlike the winter protests, the rally in Moscow was held without thousands of detainees; police vagons and stations were not overcrowded; police officers did not use violence against protesters. It seemed that the authorities had resigned themselves and decided not to interfere with those gathered to exercise their right to freedom of assembly.

But after a few days, it became obvious that this was not the case. Police visits, detentions and trials began.

Detentions of protesters after the end of the event, or, as we call them, «post factum detentions», have taken place before 2021. In 2018, OVD-Info counted 219 such cases in 39 regions of Russia; they were mostly isolated in nature: one or two people were detained in connection with one event, in exceptional cases the number of detainees reached ten. They began to be widely used in 2020 during the protests against the arrest of the governor of the Khabarovsk region, Sergei Furgal. From July to early December 2020, OVD-Info recorded 121 post factum detentions there — almost twice as many as at the protests themselves.

In 2021, a similar practice emerged in Moscow. On the day of the protests on January 31, many people were detained because of their participation in the events a week earlier. During the week after April 21, more than a hundred people were detained in Moscow, and the courts received more than 180 cases of violation of the procedure for holding a public event (under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences).

In total, in 2021, we recorded at least 454 post factum detentions. Most of them — 363 — are connected with the rally in support of Navalny on April 21. The remaining 91 arrests were related to the national protests on January 23 and 31, as well as protest events on September 20 and 25 on Pushkin Square in Moscow.

We believe that the increase in the number of post factum detentions is based on the development of technologies for monitoring social networks and facial recognition: authors of posts with information about the events are equated with the organizers, and people identified by video recordings are declared participants.

Our report is devoted to the use of facial recognition systems to restrict freedom of assembly. Although our research focuses on Moscow, according to our data, the geography of this phenomenon goes far beyond the capital.

Based on the materials of administrative cases, texts of court rulings and testimonies of detainees, we show how the authorities hide the use of facial recognition in administrative cases, how the courts perceive this fact, and what negative consequences this practice entails. In addition, we explain what needs to be changed in legal regulation and law enforcement practices to ensure freedom of assembly.

Introduction of a facial recognition system in Russia

In May 2017, the official website of the Mayor of Moscow reported that more than 3.5 thousand cameras have been connected to the Unified Data Storage and Processing Center (ECHD), including more than 1.6 thousand at the entrances to residential buildings. And already in September, more than three thousand city surveillance cameras were connected to the facial recognition system. The Mayor’s Office called it one of the largest in the world, with the Department of Information Technologies (DIT) being responsible for its development in Moscow.

In 2018, the authorities had the opportunity to conduct large-scale testing of the new technology during the World Cup. As Sergey Chemezov, CEO of Rostec Corporation, later told, about 500 cameras were connected to the FindFace Security system developed by NtechLab, which allowed detaining about 180 people in several cities. He was talking both about city surveillance cameras and cameras that were specially installed at stadiums and in the subway.

These technologies are part of the tools that the authorities have been developing for the federal program «Safe City» (it includes not only face recognition, but also, for example, urban video surveillance). In most regions, the «Safe City» began to be introduced in 2015-2016. In September 2020, NtechLab announced that it was testing its algorithms in Nizhny Novgorod and nine other major cities, though without naming them.

According to NIST data, the recognition algorithms of the Russian companies NtechLab and VisionLabs (another company whose algorithms are used by DIT for the development of the urban video surveillance systems in Moscow) hold the second and the third place in the world in terms of quality. Russia is outrun only by China.

Although the mass wearing of medical masks during the pandemic could become an obstacle to facial recognition, the developer of biometric recognition Anton Maltsev believes that this problem may have already been solved:

«The accuracy of the systems initially sagged, but not critically ― they immediately began to retrain. Roughly speaking, let’s take [retail sales], which my friends work with [in the field of recognition]. People were being tracked in the store: what people buy, where they go. And they had a problem that all the systems stopped working when the masks appeared. In a month or two, they were retrained, they got a loss of accuracy, but in the end everything worked with the masks. Therefore, if this is a medical mask, which also may be slightly lowered, it most likely works with us.»

And indeed, examining the case files of those held liable «post factum», OVD-Info found at least one case in Moscow when a person was detained on the basis of a photo and video, although in both images he was wearing a medical mask.

Activist and author of the Telegram channel “Protest MSU” Dmitry Ivanov was held liable in the wake of the protests on April 21, despite the fact that he was wearing a mask on the videos from the event.

Sources of images from protest events

Many people who contacted OVD-Info due to post factum persecution in connection with the protest events of the beginning of 2021 stated that the police did not hide that they found them with the help of photo and video cameras.

Artem Pugachev, a student, was not shown the recordings from the cameras at the police station, but they showed him the report of the officer who allegedly found Pugachev on the video. Pugachev saw the video itself only in court:

«We arrived, waited for our turn. The judge read out the prosecution statement, asked if I had any comments. I told her my position, and then we started analyzing the case materials. A disk was attached to the case file, the assistant inserted it into the computer and displayed it on the screen. In fact, this was nothing more than just a recording from an ordinary city camera. Simply people walking down the street, in a continuous stream. You see, people-people-people are coming… And then I come out and turn my face into the camera ― and at that moment, the frame freezes.»

Among those who applied to OVD-Info because of the protest event of April 21, at least 164 people noted that during communication with the police or during court hearings they were informed about the use of photo and video materials with their participation as evidence. 125 people had the opportunity to get acquainted with these materials. Learn more about the methodology.

Although this was most often reported by residents of Moscow, this practice is not limited to the capital: similar evidence was received from at least 17 other cities.

Some law enforcement officers openly reported that they had found them using the «Safe City» system. In one case, a detainee was even told at the police station about where the camera had been, filming people moving along Tverskaya Street to the Okhotny Ryad metro station on April 21.

In addition to photos and footage from surveillance cameras, the cases included footage and recordings made by police officers on the ground, as well as photos and videos from the Internet: Telegram channels, chats, personal pages on social networks, the YouTube platform.

Evidence of the use

The use of videos from an event itself does not necessarily mean the use of facial recognition technology. In administrative cases related to protest events, such materials have been encountered before: they were used as proof of the mass nature of an event or the participation of a particular person in it. There have also been cases of detentions of participants a few days or weeks after an event, but these have been, as a rule, public figures, journalists or active participants in the protests, whom police officers knew by sight.

In 2021, video recordings also became a tool for identifying participants. Firstly, this is about identifying protesters on video recordings from events using facial recognition — this is the aspect this report focuses on. In addition, recordings from cameras (for example, installed in entrances to residential buildings or the subway) allow one to further determine the location of these people in order to held them liable post factum.

The use of facial recognition technology is evidenced, first of all, by the large-scale post factum detentions and the prosecution of non-public figures, as well as the words of police officers.

In some cases, the police directly informed the detainees that they had been identified using a facial recognition system. This was told, for example, by Sergei Obukhov, a State Duma deputy from the Communist Party, who was detained in the Moscow metro after a meeting with the Communist Party deputies on September 20. The police showed him a smartphone with a screenshot that compared the video and his old photo.

Although the use of a facial recognition system to identify protesters was widely covered in the media after the January 2021 protests, the technology is rarely mentioned in official documents. We found similar mentions only in six decisions of the courts of first instance on the «rally» Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences in 2021. In four cases, the phrase «face recognition» is used by the defense, in another one «tools of personal identification through a photo» are mentioned — they are listed in the list of evidence presented by the police.

Here is how the operation of facial recognition technology is described in one of the mentioned rulings, taken from the words of a police officer:

«The camera is connected to the facial recognition system. The face is „linked“ to a certain time and indicates the percentage of similarity. Cameras were installed in the places where the public event took place. The material was compiled by him on the basis of the report of the senior operative of the 11th department of the Directorate for Criminal Investigation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia at [department address and full name of the person involved] and the video materials provided. It follows from the video that [the name of the person being tried], as part of a group of citizens chanting slogans and carrying posters, took part in the public mass event.»

The sixth case available to us, which can be linked to a facial recognition system, refers to «biometric facial identification».

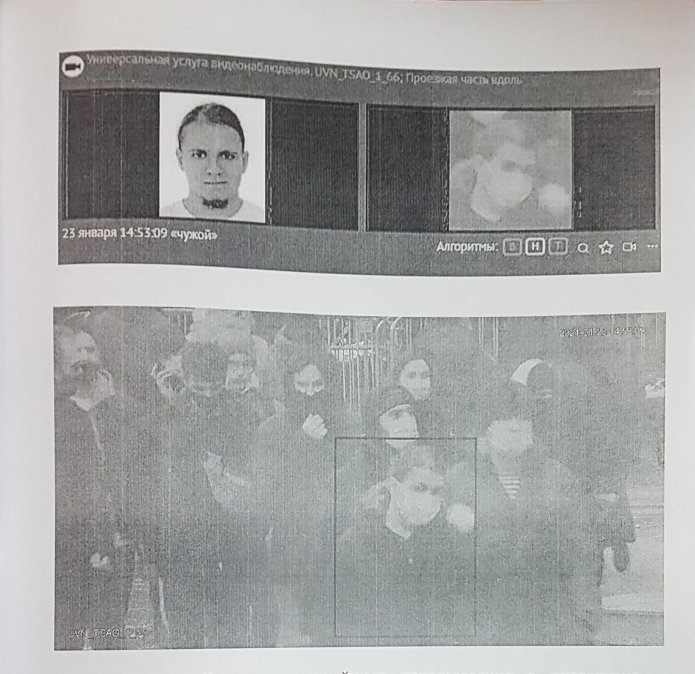

The paucity of direct evidence of the use of facial recognition technology in police reports, case files and court rulings may indicate that the police and courts prefer not to officially document this information. Nevertheless, in some documents there are indirect signs of the use of technology:

- images showing the probability of similarity as a percentage;

- mention of the Moscow «Subsystem for automatic registration of video information indexing scenarios»

- police testimonies that the participation of a particular person in an event was established by the Moscow Department of Information Technologies, which then passed this information to the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

As a developer of recognition algorithms Yuri Malkov explained to OVD-Info, at first the system is trained on a large array of publicly available photos ― for example, on the faces of famous people. It learns to compare two images and assess how similar they are to each other. «It’s not a binary yes or no. The system is trained to predict the probability of [similarity of images], ” explains Malkov.

Further, in order to identify a specific person in a video from street cameras, it is enough to show the system one or more photos with their face. The system will compare these images with the face of an unknown person in the camera footage and will give a probability of similarity in the range from 0 to 100%.

In a conversation with OVD-Info, Yuri Malkov and another developer of recognition algorithms, Egor Burkov, agreed that there are more false positive results in a poorly trained system.

Lawyer and legal adviser of the Roskomsvoboda project Ekaterina Abashina notes that there is no precise indication to be found of the percentage of similarity between two images that is needed so it could serve as a basis for any measures against a person, for example, conducting additional investigative activities or initiating an administrative offense case.

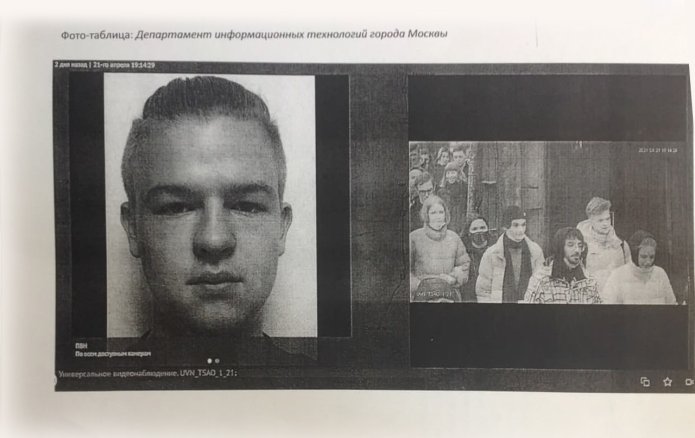

In the materials of administrative cases after rallies, images from video cameras are drawn up in the form of photo tables. A typical table looks like a screenshot of a video recording from a camera located nearby (most often city video surveillance) and a photo of the face of the alleged participant of the event. Sometimes only a screenshot is left in the materials, and the right person in the crowd is circled with a pen.

In instances where there is a screenshot of a video recording in the case files, the source may be indicated, although not necessarily: in Moscow, this is usually the Department of Information Technologies (DIT) or the Unified Data Storage Center (ECHD). In other regions, it would be the «Safe City» system. In some cases, the image shows the name of the camera, by which you can determine its location.

Sometimes the names of the algorithms used are present at the bottom of the screenshot; in rare cases the probability of similarity of images is indicated in the material.

For example, in the police report on the article on obstruction of traffic during a public event (Part 6.1 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences), issued on March 2, 2021 for the author of the Telegram channel «Protest MSU» Dmitry Ivanov, the probability of similarity of the face in the photo and video is 77,87%, and the name of the algorithm is also mentioned. Ivanov was recognized despite the presence of a medical mask.

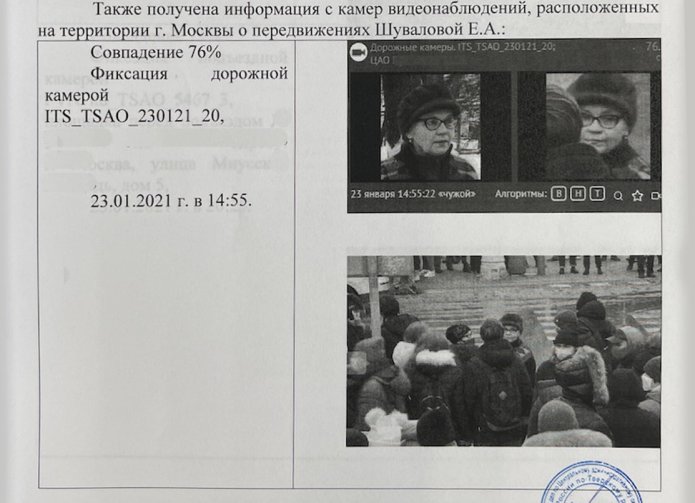

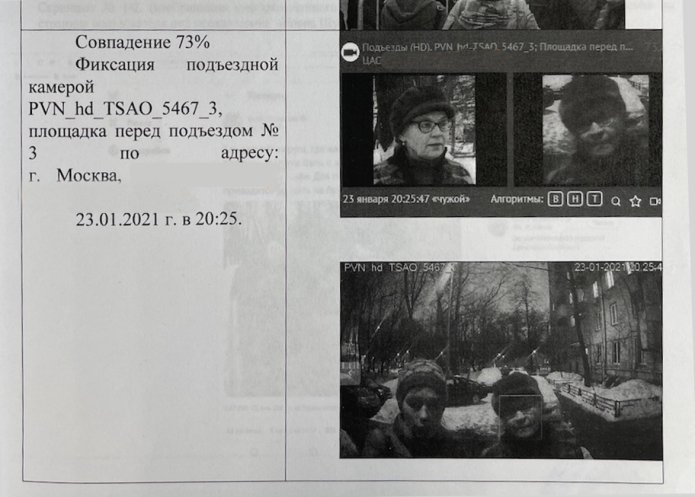

In the police report issued for the deputy of the Moscow City Duma Elena Shuvalova, the percentage of similarity of the face in the video and in the photo is present.

The case file says that the fact of Ivanov’s presence at the rally in support of Navalny on January 23 «was established with the help of PARSIVE GIS ECHD». PARSIV is a subsystem for automatic registration of video information indexing scenarios.

In 2019, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in Moscow, in an information and analytical note on the results of official activities of the Moscow police, reported that «PARSIV 2.0» is a module used in the «Safe City» for video analytics, which is also «actively used by police officers in official activities.» According to the authors of the note, the module «PARSIV 2.0» reduces the processing time of a video archive and allows to view and identify people with the help of cameras from entrances of residential buildings.

We found mention of the «PARSIV» system in seven more court rulings concerning the prosecution of citizens in connection with protest events. «PARSIV» also appeared in some rulings issued in connection with violations of sanitary and epidemiological norms in 2020.

In one of the available to OVD-Info cases against a resident of Nizhny Novgorod, the screenshot of the video also contained an inscription indicating the probability of similarity: 78%. Similar percentages of similarity probability are also present in some other case materials.

Image sources

Since at least 2012, participants of the protest events have been illegally photographed at police stations. This practice has managed to take root and has become widespread. For example, those detained at the rally in support of Alexei Navalny on April 21, 2021 in St. Petersburg reported to OVD-Info about photographs being taken in 24 of the 48 police departments. In some cases, detainees are coerced by threats or force.

Illegal photographing of detainees is one of the most common violations occurring at police stations.

Alexey Shlyapuzhnikov, an expert on security and identification technologies at Transparency International, notes that such photos can be used for recognition:

«The system includes the modules „Sherlock“ — search through the passport database — and PSKOV („Search engine of the category of special importance“), which also works with social networks. „Sherlock“ and PSKOV are connected: the more photos of a person in this system, the easier it is to find them — a photo for a national ID or a passport, in a criminal case, or a person was detained and taken to a police station. Therefore, everyone is being photographed intensively during detentions. The more high-quality photos from different angles posted on a social network, the easier it is for the system to recognize a person. Uploads from „Sherlock“ get into cases without links to social networks, only with a passport photo. But, as far as I know, all photos from the personal file of a citizen of the Russian Federation are used for identification by video.»

However, OVD-Info has not yet been able to detect documented cases of the use of photographs taken at police stations for facial recognition. Of the 164 people who applied to OVD-Info, only 37 (23%) were previously detained for participating in other protest events, and 16 (10%) of them were photographed at the station during previous detentions. The low proportion of such cases indicates that photographs from other sources were usually used to establish identity.

Egor Burkov suggests that the basis of search databases may be formed by passport photos:

«For a lot of people, the authorities have at least one copy of some document; I am sure that now the basis of the database is passport photos. But if a person, for example, received a passport 15 years ago and since then has had no more dealings with the state, then they might not have a single picture of them. Scanning social networks is too inconvenient: even if the right account is found (which is already not completely trivial), there may be other people in the posted photos, ” Burkov believes. «Therefore, when the state once again asks for a photo ― for example, now on the «State Services» electronic portal when arriving from abroad ― it is definitely used to improve the database.»

Working with cases in which participants of the events were held liable post factum, OVD-Info found that photos from passports or social cards are used for comparison; in some cases, these are photos from already invalid passports. The protesters who applied to OVD-Info after the April event also talked about the use of photos from national (external) passports and social networks.

In the police report issued for an alleged participant of the protest event of April 21, his photo from the social card (on the left) was used for comparison.

In the case files and court rulings available to us, extracts from databases used by police officers to store passport photos were mentioned:

- Automated System «Russian Passport», which, in fact, stores data about invalid passports;

- Information-search engine «Pathfinder-m» (Sledopyt-m);

- An integrated database of regional or federal levels (IBD-R and IBD-F), which stores passport information of citizens, information about the place of residence, about cases of prosecution in the past;

- Public Order Protection Service (SOOP).

To compare a participant of the winter protests with the face of Elena Shuvalova, her photo from an invalid passport was used, from the AS “Russian Passport”.

Experts believe that for greater accuracy, the police can take into account other data: for example, by tracking passengers who have visited a particular subway station at a certain time with the help of transport cards, or by establishing location of people using telephone billing.

«This is done in order to compare not with the multimillion population of the whole of Moscow, for example, but with tens of thousands who were in this place according to phone billing. This should greatly increase the accuracy of the search using facial recognition, ” says Anton Maltsev, head of Computer Vision and Machine Learning.

Initiation of a case

If a person who visited a protest event is captured by a video surveillance camera, an administrative case may be opened against them already after the event. According to the experts we interviewed, this probability increases if a participant of the event looked directly into the camera ― in this case, it is easier for the algorithm to recognize the face.

So far, a small proportion of protesters face post factum detentions. In fact, even if we rely on official data (where the mass nature of protests is often underestimated), about six thousand people participated in the protests of April 21 in Moscow, that is, significantly more than the number subsequently brought to administrative responsibility.

OVD-Info is aware of the prosecution both after two days and after more than five months after an event.

The trajectory of the initiation of the case may differ. In some cases, according to the court rulings we found, the police unit itself turns to the sources of video recordings (in Moscow, it is the Department of Information Technologies or the Unified Data Storage Center, in other cities ― the Hardware-Software Complex «Safe City») with a request; in other documents it says that the unit «received» the video.

In at least one case, an employee of the Center for Combating Extremism, who acted as a witness in court, stated that the footage from April 21 was sent by the Department of Information Technologies to the CCE already with a list of potential protesters. Whose initiative it was initially — the police or the DIT — remained unknown.

It is unclear from the court rulings whether there is any specific algorithm and order of interactions between the police and the DIT, ECHD or «Safe City» systems. Apparently, all three of the latter structures can provide records at the request of the security forces, but in Moscow, the DIT acts as their main source.

According to the verdict of the Moscow City Court on the appeal case against the decision of the judge of the Zamoskvoretsky District Court, the Department of Information Technologies is a «functional executive authority» that performs «functions for the development and implementation of state policy in the field of information technologies» and acts as the operator of the ECHD, «the state customer of works (services) related to the creation and operation of the ECHD, as well as the coordinator of activities for connecting information systems, users of information about video surveillance facilities and providing information to the ECHD».

Thus, all video recordings and images from city surveillance cameras in Moscow are stored in the ECHD, and it is the DIT, apparently, that uses facial recognition systems and transmits this data to the police. From the same verdict:

«Employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in Moscow, who have been granted access to the ECHD, in order to fulfill their official duties, use a video analytics system based on the ECHD to identify persons who are on the federal wanted list, persons who are prohibited by court order from attending mass events, persons under administrative supervision.»

At the same time, the court claims, the DIT does not carry out activities aimed at establishing the identity of a particular citizen:

«The ECHD lacks personal data of citizens (full name, etc.), as well as biometric personal data (iris, height, weight, etc.), which are necessary to establish the identity of a citizen.»

It is not known whether the range of the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ units that can request records is somehow limited. The court rulings mention district commissioners of police departments, public order departments, the Center for Combating Extremism, the Directorate for Criminal Investigation (for example, the the Directorate for Criminal Investigation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in Moscow) and the Bureau of Special Technical Measures (BSTM). In a significant part of court rulings, reports explaining the appearance of the video footage in the case materials are written by employees of the Center for Combating Extremism. One of the documents stated that the video was obtained by the police as part of a check through the CUSP (Register of reports on crimes, administrative offenses and incidents). In the materials available to OVD-Info, the study of video recordings during investigative activities was also mentioned.

Summoning or bringing in to a police station

After identifying an alleged participant of a protest event, the police makes efforts for them to arrive at the station where an administrative offense report is issued; then the case is considered by the court. At each of these stages, events can develop in different ways.

The specificity of being held liable with the use of facial recognition is that a person learns about the police intention to issue a report quite unexpectedly. For this, they can be forcibly delivered to a station or summoned on a voluntary basis. In some cases, the police can put pressure on a person both before and after detention.

People identified by cameras after the protest of April 21 most often reported police visits to the official residence address, although sometimes officers also established the actual living address.

- In this way, a resident of Moscow was attempted to be held liable because of the protest of April 21. First, the police came to his father’s apartment, where the rally participant himself was not registered. Then the police officers came to the place where he actually lived, and when they did not find him there, they began to call by phone, demanding «to come to the police station urgently.» After arriving to the station, the man was detained.

- According to our data, at least one participant of the protest rally was visited while he was sick with the coronavirus. The police forced the man to leave the apartment and on a bench near the house issued a report for participating in the event (Part 5 of Article 20.2 of the Administrative Code), showing the case materials with photos and screenshots of videos with him in a crowd of protesters.

In another case, the security forces arrived at a country cottage. To many people, the police came home early in the morning or late in the evening.

When people refused to open the door or come to a police station, various coercive measures could be applied to them. In some cases, people reported to OVD-Info the use of force or threats from the police.

- In Nizhny Novgorod, on April 23, a local resident was detained: men in civilian clothes met him near the house, took away his phone without explanation and pushed him into a van, and there they held him face to the floor until he was taken to the police station.

- One of the participants of the protest rally in Moscow told OVD-Info that the police first had been inviting him to the station for a long time to issue a report, and when he did not show up, they came to his house and, according to his wife, began to «break» into the apartment. When the man arrived home, he was detained with the use of force and taken to the police.

- For another resident of Moscow, the policemen, including some in plain clothes, waited for a week at the entrance of the house, and also constantly called on a mobile phone.

- Sometimes the security forces deliberately misled potential detainees. In May, an unknown man called a resident of Moscow who teaches rock climbing. He said that he wanted to send his child to the club, and asked for a meeting where the woman was met by the people in civilian clothes and taken to the police station for the issuing of the report.

- Another method of influencing the protesters was the pressure on relatives. For instance, a Moscow resident told OVD-Info that the police called her to the police station to issue a report, and when she refused, they came to her 81-year-old father and there they threatened to come with a police team if she did not come. The woman had to come to the station herself.

- In another case, according to our data, for the sake of meeting with the alleged participant of the event, the security forces misled her with the help of other people. A student from Moscow was called to the police station for the issuing of a report; she refused to come without an official summons. Then the dean of the university called her and asked her to come in. When the student showed up, the police were waiting for her along with a university employee.

People whom the police suspected of participating in the protest events were detained right at the workplace, removed from university classes, one person was taken right from a lesson at school. There were cases of detentions in cafes, on the street, in the subway, on the train platform and on the train:

- According to the data available to OVD-Info, at least one person was removed from the train because he was suspected of participating in the protests on April 21. According to the detainee, the security forces had four videos, according to which they could not accurately identify the participant of the protests. The man together with the lawyer wrote an explanatory note that he had not participated in the rally, and he was released.

- Another person told us that he was detained on the train platform immediately after arriving in Moscow from St. Petersburg. Before that, the police came to his home for several days at the official address of his residence; they also looked for him at the place of actual residence. During the arrest, the law enforcement officer showed the man on the phone a video from the rally, on which he was captured.

- Several people were detained post factum when exiting the subway. After the elections on September 17-19 and the protests following their results, members of the Communist Party faced persecution in Moscow. Some of them were detained right in the subway; at least one detainee was informed by the police that they had found him by facial recognition, and was showed a comparison of a screenshot of the video and a photo on the phone.

- A few days after the protests of April 21 in Moscow, a district police officer approached a gastroenterologist on the street, detained him and took him to the police station to issue a report. To another resident of Moscow, the police came home several times, summoning her to the police station, and eventually detained her on the street, threatening to drag her into the car by force. In Khabarovsk, a local resident was detained after the protest rally of April 21, when he got into a car early in the morning to take family members to work and study. A police car blocked their way.

Detentions on platforms, in cafes and in rented apartments may indicate the use of movement tracking systems around the city against the persecuted participants of the protests. Records from an CCTV at residential entrances can be used for this search: for example, in the materials of the case of Dmitry Ivanov, there were videos from the entrance CCTV of the house where the activist lives.

In the materials of the case filed against Elena Shuvalova, there was a screenshot of a video obtained from the entrance CCTV of the house where the deputy lives.

- According to the data available to OVD-Info, one of the participants of the protest event, who lives in Moscow, was called to the place of registered residence to issue a report. At the station, a policeman showed him a picture from the entrance CCTV from the WhatsApp application on his phone. Although the screenshot was not attached to the case file, what was happening was accompanied by the words, «We know where you live.»

- Vladimir Zalishchak, a municipal deputy of the Donskoy district of Moscow, was detained on February 2 at the Krylatskoye metro station because of his presence at the rally on January 23. The report stated that «the Face Control facial recognition system installed on the validator of the eastern lobby of the Krylatskoye metro station identified a citizen [full name] who was monitored as a person who violated the established procedure» for holding a protest event.

Of the 164 people interviewed by OVD-Info after the protests of April 21, 33 were released without a report, because, for example, there were technical problems or it was impossible to show the video at the station, or when the police found it difficult to identify the protesters in the images with people who came to the station.

In some cases, people had to write explanatory notes that they were not on the video; in others a lawyer managed to prove that his client had been in another place at that time. It also happened that a lawyer had to bring two witnesses who confirmed that his client had not been at the rally.

Most of the respondents of OVD-Info (99 out of 164 people) were charged with violating the procedure for holding a public event — Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences. Most often, it was about the relatively mild 5th part of this article, which concerns ordinary participants of an event and which does not involve administrative arrest. Less often, parts 6.1 (on obstruction of traffic or vehicles) and 8 (on repeated violations of the law on rallies) were used — they are the ones that do provide for arrest as punishment. In addition to Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences, other articles were also applied: we know of at least two cases under Article 20.6.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (non-compliance with the rules of conduct under a high-alert regime) and one case under Article 19.3 of the Code of Administrative Offences (disobedience to a lawful order of a police officer).

In the case when a report was issued under an «arrest» article, many detainees were not released immediately, but were left at the station until the trial. Artyom Pugachev, a student who was taken to the police from the dormitory, was kept at the station for two days, and after that he was placed under administrative arrest for 10 days.

- Five days after the events of April 21, Professor Alexander Aghajanyan of the Russian State University of the Humanities was detained in Moscow. He was kept at the police station overnight, despite the fact that he has asthma and doctors were called for him. The next day, the court found him guilty of participating in a rally that had obstructed vehicle movements (Part 6.1 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences), and imposed a fine of 20 thousand rubles on him.

- Even if detained post factum, six months after a protest, a person can be kept at the station until trial — for example, for 48 hours. This happened to Oleg Yurasov, a resident of Moscow who was detained in September in connection with the protest rally of January 23, and fined 150 thousand rubles by court.

In court: punishments, terminations and returns

As well as people detained directly at protests, those who were detained post factum are likely to face a fine, community service or administrative arrest. OVD-Info knows of at least one case when post factum detention led to a rather serious punishment by administrative standards: under the article on repeated violation of the law on rallies (part 8 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences), the Izmailovsky District Court arrested a participant of the protest on April 21 for 25 days.

It also has happened that a person was found on video, but the court has returned the case to the police or even closed it.

For the period from January to July 20, 2021, among the available cases that contain signs of the use of facial recognition, we managed to find 6 closed and 10 returned to the police to eliminate shortcomings (more about the methodology). All the decisions on the closure of the proceedings were made by one judge of the Zelenograd District Court of Moscow in one day. The same court returned one more case to the police; the Perovsky District Court returned five cases to the police.

The reasons for the closure of the case in the resolutions most often indicated errors in the reports, the absence of the offense and the expiration of the statute of limitations. Sometimes the cases were closed by the police themselves — due to the fact that they did not find the person in the videos and photos. In some cases, the judges refused to consider the identification by the video recordings as sufficient evidence. For more information about this, see the section «Registration of materials of administrative cases».

Almost always, the courts of second instance left the verdicts unchanged. Only in some cases did the courts close the cases considered in this report: the reasons for this were errors in the reports or the statute of limitations.

Facial recognition system in the context of freedom of assembly

By itself, the collection of data on the participants of the protests by the state creates the risk of politically motivated persecution.

The UN Human Rights Committee drew attention to this problem in 2020. According to the Committee, there is a critical issue of «independent and transparent scrutiny and oversight over the decision to collect the personal information and data of those engaged in peaceful assemblies and over its sharing or retention.» These Comments also apply to Russia as a party to the International Covenant.

In 2020, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet also noted the problems associated with the use of street video surveillance systems and facial recognition systems that arise precisely in the context of freedom of assembly and expression in her report on the impact of modern technologies on human rights.

- This is, first of all, depriving participants of a certain degree of anonymity, which is part of a collective action, and mass interference in people’s privacy, which occurs due to the indiscriminate face recognition process — all people who are on the street during a protest are subject to the threat of identification by the authorities. As a result, the feeling of constant observation and the possibility of such identification has a deterrent effect on potential participants of assemblies, who may limit themselves in expressing opinions or even refuse to exercise their rights to gather and express themselves.

- «Authorities should generally refrain from recording assembly participants, ” the document notes, referring to the OSCE Guidelines. «As required by the need to show proportionality, exceptions should only be considered when there are concrete indications that serious criminal offences are actually taking place or that there is cause to suspect imminent and serious criminal behaviour, such as violence or the use of firearms. Existing recordings should only be used for the identification of assembly participants who are suspects of serious crimes.»

These considerations should be taken into account by the legislator when establishing the legal framework for the issue, and by the courts that deal with a particular case, correlating the balance of various rights and interests and assessing the negative effects on the fundamental right to freedom of assembly.

In January 2021, Advisory Committee to the Council of Europe developed guidelines for face recognition technologies with regard to The Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, which has also been ratified by Russia. In particular, they establish minimum requirements for the legislation on facial recognition systems:

- detailed explanation of usage examples and its purpose;

- some reliability and accuracy of the algorithm used;

- the retention duration of the photos used;

- the possibility of auditing these criteria;

- the traceability of the process.

In addition, the Committee notes that the use of publicly available images to identify individuals or create databases cannot be legal solely on the basis of their public availability — that is, if the photos are posted on social networks. The authorities must ensure that such images are not used without a proper legal basis — for example, only if serious crimes are suspected.

The need for transparent legal regulation of the use of street surveillance cameras was also noted by the Venice Commission, an expert body for monitoring legislation and law enforcement practice in the field of human rights under the Council of Europe. A positive experience, according to the Venice Commission, is the establishment in some countries of special independent bodies that monitor the compliance of state regulation and practice with international standards in the field of personal data protection.

In the practice of the European Court of Human Rights, there are still no legal positions on the use of a facial recognition system in relation to participants of protest events.

In early 2020, lawyer Alexandra Rossius filed a complaint with the ECHR in connection with the detention in the Moscow metro of activist Nikolai Glukhin, who had previously held a picketing with a cardboard figure of Konstantin Kotov, who was accused under the «Dadin article» (212.1 of the Criminal Code). The evidence against him included recordings from CCTV cameras in the subway; Glukhin himself suggested that he had been identified using facial recognition. According to the activist, facial recognition technology was used to search for him. On June 23, 2021, the ECHR communicated the complaint.

Lawyers of the Interregional Association of Human Rights Organizations «Agora» raised questions before the ECHR about the violation of the right to respect for private and family life, restriction of freedom of assembly due to the mass use of the facial recognition system without the consent of people. The applicants, activist Alyona Popova and politician Vladimir Milov, had previously unsuccessfully appealed to Russian courts against the use of video surveillance and facial recognition systems during a rally in support of the defendants in the «Moscow Case» in September 2019.

At the same time, the ECHR has formulated a number of important rules in various decisions that can also be applied to the use of facial recognition.

- Even in public space, there may be a violation of the right to private and family life, including in the case of the use of CCTV cameras, especially when it comes to the preservation and transmission of video recordings and images, processing them to identify a particular person, as well as in the case of the use of video recordings for purposes beyond the limits of ordinary expectations.

- The use of video surveillance should be justified by a legitimate need and proportionate to this need, as well as regulated by law in such a way that it is clearly established in which cases and to what extent video surveillance is permissible, for how long, how the decision on video surveillance is reviewed and appealed.

The complaint provides an example of a regulation in force on the territory of the European Union prohibiting the collection of biometric personal data without the direct consent of people, which prevents the mass use of the facial recognition system.

In the judicial practice of the EU member states, there have been decisions where the use of a facial recognition system was recognized as violating the right to freedom of expression and assembly. In addition, the use of surveillance tools in public space may be recognized as a violation of the right to privacy.

In addition to general international problems, the following legal issues are relevant in domestic realities:

- the problem with the retention time of recordings from cameras, the regulation of access to them and, as a result, the practical possibility of data leakage and their arbitrary use;

- processing of biometric data of citizens without their consent;

- use and evaluation of the results of using the facial recognition system as evidence in cases of administrative offenses;

- lack of legal protection mechanisms for victims of illegal use of the facial recognition system.

Below we take a closer look at all these problems.

Storage and access to data from city cameras

In Moscow, data from many city surveillance cameras are flocked to the ECHD, owned by the Department of Information Technologies (DIT) of the city.

The range of subjects that can access the data of city surveillance is extremely wide: «Access to ECHD for information in real time is provided to the highest officials of the subjects of the Russian Federation and persons authorized by them, and to the federal bodies of state power, bodies of state authority of the city of Moscow, organizations in order to carry out their functions and powers in accordance with their purview». In addition, the circumstances under which the use of ECHD is possible are not described clearly — which means that all the listed persons and authorities have the right to access the described data almost limitlessly.

DIT emphasizes that law enforcement officers have access to the city’s video surveillance system only from their workplaces and «for the purpose of exercising their powers.» Access is carried out through personal accounts, «when issuing which users sign a document on non-disclosure of confidential information, as well as on the inadmissibility of transferring the login and password to third parties.»

All facts of access to the information contained in the ECHD, including the facts of the demonstration of archival information and the facts of its preservation on external electronic media, are recorded in the logs of access to information.

Formally, the storage period of data from cameras is limited. As indicated on the DIT website, for entrance and courtyard video surveillance cameras, this is five calendar days, for video surveillance cameras in places of mass gatherings of citizens — thirty. The ECHD access regulation of 2015 also specifies that if the data is reserved, they are stored in the database for an additional thirty days «after which they are automatically deleted.»

- Reports for participants of the winter protests have continued to be issued more than six months after the events. The last known to OVD-Info case occurred on November 25.

In addition to access to city surveillance cameras, police officers have at their disposal a number of databases with information about passports, the place of registration and the administrative liability record of specific people with passport photos (for more information, see the section «Image sources»).

These two types of data (videos from events and photos of a person with a link to an identity) are enough for mass facial recognition — they are a key tool for identifying and searching for alleged participants in the protests.

The problems with storing data from video cameras are clearly illustrated by the case of a resident of Moscow, Anna Kuznetsova, that was taken by lawyers of the Roskomsvoboda project.

In the summer of 2020, Kuznetsova discovered a service on the darknet that provided data from city surveillance cameras which captured a person of interest to buyers. As part of the experiment, the woman ordered data from her own image. After the payment, she received a report with the result from 79 metropolitan cameras, indicating the addresses where she had been during the last month. As part of the criminal case, two metropolitan police officers pleaded guilty and received court fines of 10 and 20 thousand rubles (the amount of fines is comparable with the cost of one «search by the face»). The court closed the case itself.

The Kuznetsova case shows that the stored video data does not have reliable protection and becomes a commodity on the black market, or becomes available to the public as a result of leakage.

The lawyers of Roskomsvoboda demanded a moratorium on the use of the facial recognition system until the safety of citizens from abuse is ensured.

Processing of biometric data

«The use of facial recognition technology against protesters is illegal, because this technology is in a gray area of regulation, and there are no clear and specific rules on when it is permissible to use it, ” Ekaterina Abashina, a lawyer and legal advisor of the Roskomsvoboda project notes. «And this, in particular, is due to the fact that facial recognition technology processes biometric data of citizens, and according to the law on personal data, this can be done either with the consent of the citizen themselves, or in cases that are established by federal laws. And there are no [such] federal laws that would establish as an acceptable case the scanning of people during rallies in order to impose administrative fines on them.»

The position of the courts and other authorities that consider it legitimate to use facial recognition to search for protest participants is based on three main arguments:

- face recognition of protest participants is not the processing of personal data.

- cameras record information about territories, not about people.

- the facial recognition system is used to maintain law and order or in other public interests;

All these arguments seem to us untenable. Below we explain why.

Face recognition is not the processing of personal data

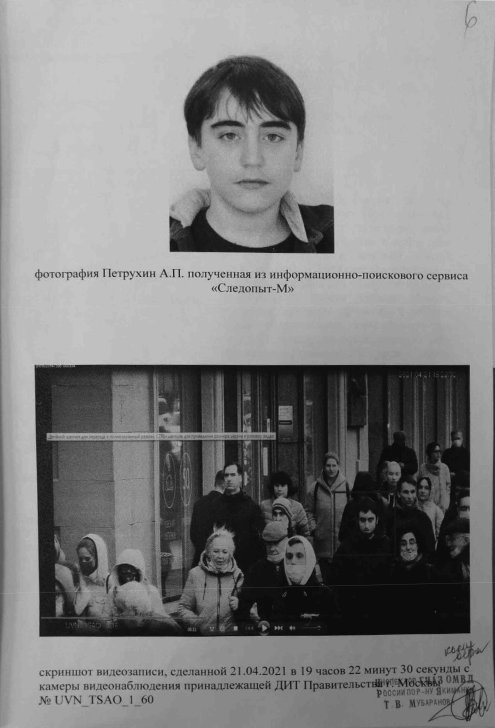

On April 30, a report was issued against a resident of Moscow, Andrei Petrukhin, under Part 6.1 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences — he was deemed a participant in the rally of April 21. As evidence, the police used a photo table and a video recording from the cameras; the man was fined. In an appeal verdict on May 18, the Moscow City Court recognized the use of facial recognition technology in this case as legitimate. According to the court, the DIT process based on ECHD, despite the use of a facial recognition system, operates only with images of a person, comparing them; and the identification of a citizen is allegedly carried out by a police officer. According to the court, the facial recognition algorithm does not work with personal data:

- «The facial recognition algorithm used in the ECHD compares the image coming to the ECHD from video cameras with a photo provided by a law enforcement agency. When processing the corresponding images, they are compared for the presence / absence of matches. The personal data (full name, etc.) of the persons sought are not transferred to the Department [of Information Technologies], since the Department does not have the technical and legal ability to compare them.»

The courts' claims that facial recognition is not the processing of personal data contradicts the basic concepts contained in the Federal Law «On the Processing of Personal Data». The provisions that a person’s photograph refers to biometric personal data are contained both in the Federal Law No. 152 “On Personal Data» and in explanations by Roskomnadzor.

- The Federal Law refers to biometric personal data information that characterizes the physiological and biological characteristics of a person and on the basis of which it is possible to establish their identity and which are used by the operator for this purpose.

- In the explanations of Roskomnadzor, it is indicated that such «characteristics of a person» include, in particular, their images (photo and video), which allow to establish their identity and are used by the operator to establish their identity.

- According to the position of Roskomnadzor, before the transfer of photo and video data for identification, they are not biometric personal data, since they are not used by the operator (the owner of the video camera or the person who organized its operation) for such purposes. However, they become biometric personal data if they are processed in order to establish the identity of a particular individual.

The probability of similarity of images, which is determined using the facial recognition system, leads to the identification of a citizen and is used by the authorities for this purpose. Therefore, we believe that in this case, the use of a facial recognition system entails working specifically with a person’s personal data without their consent.

The Council of Europe in the latest amendments to The Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data has included biometrics in special categories of data, the processing of which requires particularly strict conditions. At the same time, biometric data is defined in Article 6 of the Convention as data that uniquely identifies a person.

According to Russian legislation, the processing of biometric personal data is not allowed without the written consent of the person themselves.

There are exceptions to this rule, in particular, investigative activities and the administration of justice. However, these exceptions do not apply to the powers of the police in cases of administrative offenses: justice is dealt with only by the court, not the police, and investigative activities are carried out only in the case of a crime provided for by the Criminal Code. We tell you more about this in the section «Investigative activities and cases of administrative offenses».

Cameras monitor the territory, not the people

Another argument that the authorities use is that the cameras are monitoring the territory, not the people.

- In response to the appeal by OVD-Info on the illegitimacy of the use of facial recognition, the Commissioner for Human Rights in Moscow, Tatyana Potyaeva, referring to the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, stated that the consent of a citizen to the processing of personal data is not required in cases when «the image of a citizen is obtained when footage is created in places open to free access, or at public events.»

- According to the Moscow City Court, «in itself, obtaining an image of the applicant while staying in the territory falling under the surveillance sector of a specific camera installed to monitor the environment in the center of Moscow is not a way of collecting personal (biometric data), since it was not used directly to determine the identity of the applicant.»

This argument seems to be untenable, since the videos show people whose faces are eventually recognized. That is, for the purposes of using the system, it is the image of a person, and not the territory, that becomes the main object.

Face recognition is used in the public interest

Considering the case of one of the alleged participants of the April 21 rally in Moscow, the Savelovsky District Court pronounced him guilty, referring in the verdict to the Federal Law «On Police» and stating that law enforcement officers in the framework of criminal investigations and in relation to administrative proceedings may request «necessary information» from various authorities.

At the same time, according to the court, «the use of facial recognition technology in the city video surveillance system fully complies with the requirements of current legislation, is aimed, in particular, at protecting law and order, ensuring security and providing employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in Moscow with access to the ECHD for the above purposes to perform their duties» and does not violate human rights to privacy.

Moscow Commissioner for Human Rights Tatiana Potyaeva is in solidarity with the courts and believes that «the use of this technology and its use by law enforcement agencies are not arbitrary, but have the purpose of ensuring the safety of the population of Moscow and registering offenses.»

Both the Commissioner and the Moscow City Court refer to paragraph 1 of Article 152.1 of the Civil Code, according to which a citizen’s consent to the use of their image is not required when it is carried out in the state, civic or other public interests or when such an image is not the main object of use.

Meanwhile, the Civil Code is applicable to civil legal relations, and the use of images of citizens by law enforcement officers is not regulated by them.

The legitimate purpose of maintaining law and order does not exclude that the invasion of the sphere of rights and freedoms of citizens should be clearly prescribed by law. And the law does not contain norms that would allow the processing of personal data without the consent of a citizen in the context of the Code of Administrative Offences.

At the same time, the lack of mass application of facial recognition technology to many other types of offenses (such as crossing the road in a wrong place or stowaway) indicates that the main purpose of using this technology is not to protect public interests, but to persecute political opponents of the authorities.

Registration of materials of administrative cases

If a report on an offense against a person was issued post factum, and not after a person being detained at an event, this often means that their identity was not established on the spot (although sometimes the police write down passport data, for example, during picketing). Therefore, law enforcement officers need to explain the process behind a comparison of identity between the person captured on the video and the person they are trying to held liable because of participation in an unauthorised event.

Having studied the available materials, OVD-Info has come to the conclusion that there are two main ways for the police to do this:

- an indication that the identification of persons occurred during «investigative activities»;

- a police officer’s report in which they state that they «identified» a specific citizen on photos and videos, without further explanation.

In none of these cases does the police «on paper» admit that facial recognition technology was used in any way to determine a person’s identity. It is possible that law enforcement officers prefer not to document the use of facial recognition once again precisely because it is in the «gray zone» of Russian legislation.

Investigative measures and cases of administrative offenses

The use of facial recognition can be attributed to the following types of investigative activities: collecting samples for comparative research, observation, identification of personality, obtaining computer information.

- So, in an administrative case initiated against a Moscow resident in connection with the April 21 rally, referring to the Federal Law «On Investigative Activities», the police request to conduct a portrait study of her image in a photo from the Pathfinder-M database and on a video obtained by law enforcement officers from DIT. The case materials are available to OVD-Info.

Following the protest event on April 21, a report was issued against the student, in which a photo from the Pathfinder-M database was used.

Investigative activities are included in the exceptions provided for in paragraph 2 of Article 11 of the Federal Law «On Personal Data»:

«Without the consent of the subject of personal data, the processing of biometric personal data may be carried out <…> in cases provided for by the legislation of the Russian Federation <…> on investigative activities.»

That is, in theory, during the investigative activities, police officers can process personal data without a person’s consent.

However, according to the position of the Constitutional Court, investigative activities may be carried out only on the basis of the signs of a crime provided for by the Criminal Code:

«If in the course of investigative activities it is found that the situation concerns not a crime, but other types of offenses, then <…> the case of operational documentation is subject to termination».

At the same time, according to the Constitutional Court, investigative actions can be carried out when a criminal case has not yet been initiated, but «there is already certain information that must be verified (confirmed or rejected) during investigative measures, according to the results of which the issue of initiating a criminal case will be decided.»

In 2020, the Constitutional Court also expressed the opinion that if, as a result of the investigative activities, not a crime was detected, but an administrative offense, this in itself «does not indicate the illegality of this investigative activity, the unreliability of its results and the inadmissibility of their use in proving an offense in accordance with the relevant procedural legislation.» A similar position was expressed by the Supreme Court of Chuvashia. However, both cases concerned only one of the types of investigative activities — test purchase; in the context of rallies the issue was not considered

The Constitutional Court did not see any problems in the practice of using the materials of investigative activities in administrative cases. However, this does not mean that in each specific case the courts of general jurisdiction should not check the legality and validity of the actions of the executive bodies.

According to the Code of Administrative Offences, it is not allowed to use evidence obtained in violation of the law — in this case, the law «On Investigative Activities». And according to this law, the basis for the investigative activities is «information that has become known to the bodies carrying out investigative activities about the signs of an illegal act being prepared, in the process of being committed or already committed, as well as about the persons preparing, committing or having committed it, if there is not sufficient data to resolve the issue of initiating a criminal case.»

In our opinion, in the context of the rallies under consideration, the police had no grounds for conducting investigative activities, since initially there were no signs of a crime committed and no signs of an examination for a criminal case. As a consequence, the information obtained during the investigative activities was not admissible evidence in cases of administrative offenses. The legality of conducting investigative activities in a particular case should be assessed by the courts, but in practice this does not happen.

Officer’s report without reference to investigative activities

Special attention should be paid to the method of enclosing photos and videos through a police officer’s report; the one who allegedly «identified» a specific citizen on the images.

At the same time, in such cases there are no references to investigative activities, and there are also no answers to the question of how exactly it was possible to identify a particular person. Police reports may contain indications that videos and photos were obtained, for example, from the DIT, but the reasons for this are not always indicated. Moreover, in many reports there is the wording «a person similar to».

Such evidence and their registration in the materials of cases of administrative offenses in this way are evaluated differently by the courts.

In a number of cases reviewed by OVD-Info, the courts did not summon police officers for questioning, and the method of identifying persons simply remained undisclosed. Thus, the courts accepted the police report itself without additional explanations as sufficient evidence.

Nevertheless, in some cases, the courts have been critical of such evidence.

The reason for returning cases to the police was, for example, that it was impossible to identify a person with the help of a video provided by law enforcement officers. In the Nagatinsky District Court of Moscow, the expert, after reviewing the case of a Moscow resident for the rally on April 21, could not identify him with the person appearing in the materials. In the Babushkinsky District Court, the judge stated that it was impossible to see the participant of the event in the video, and therefore the fact of the violation remains unproven. For the same reason, the Zelenograd District Court did not consider the case of a person who was tried for the protest event on April 21.

The judge of the Perovsky District Court of Moscow in the decision on the return of the case indicated that the materials do not explain how the identity of the citizen held liable was established:

»… it does not follow from the report of the operative of the 1st department of the 8th department of the Directorate for Criminal Investigation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in Moscow, exactly how it was established that the person recorded on the video is exactly [FULL NAME]… as well as from the reports of the police prescint comissioner of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia in the Ivanovskoye district of Moscow, it does not follow on the basis of what concrete evidence officials concluded that [FULL NAME]… is the person who committed the offense imputed to her.»

According to the judge, the only thing that follows from the photo and video materials is that «passers-by are walking on the sidewalk»:

«it has not been established who exactly of the recorded persons is (and whether they are at all)… [FULL name]… the identity of these persons is not known to the court, the court does not have any means to identify these persons, specific sources of identification of the citizen depicted in the photo and video are not provided to the court.»

The judge also points out that the police officers who compiled the report were not eyewitnesses of the incident, which means they cannot say whether the accused had been at the rally or not. At the same time, the citizen herself, whom they tried to held liable, denies her presence on the video, as well as her presence at the event.

The following conclusion can be drawn from the decisions on the termination or return of cases: the key problem for holding protesters liable with the help of face recognition is the issue of identifying a person in the image and identifying a specific person with this image.

Without mentioning this technology or specific investigative activities, a gap appears between a person in court and a citizen in a video or photo: it becomes impossible to prove that this is one person.

Legal protection measures

Lawyer Ekaterina Abashina notes that in cases of administrative offenses, almost the only measure available to defence is to request the exclusion of inadmissible evidence from the case materials. The satisfaction or ignoring of such a request remains at the discretion of the judge.

On the example of the case of Anna Kuznetsova it becomes clear that filing administrative lawsuits against the Ministry of Internal Affairs or relevant city departments does not yet lead to a change in the position of the city authorities. The arguments of the authorities boil down to the fact that the facial recognition system is used for legitimate purposes of ensuring public safety, and the collected data itself does not contain all the elements to identify a particular person — Kuznetsova herself provided the attackers with her photo.

A particular problem is that a person whose biometric data is illegally processed using a facial recognition system may not find out about the violation, since the fact of using the technology is not disclosed in the case file. Consequently, it will be difficult to appeal it.

In 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of opinion and expression, David Kay, noted «the lack of judicial oversight, remedies, causes of action, enforcement and data preservation [for data obtained as a result of the use of surveillance systems]». Due to the high degree of threat to freedom of expression and privacy and the lack of transparent global and state regulation, the Special Rapporteur recommended that countries «impose an immediate moratorium on the export, sale, transfer, use or servicing of privately developed surveillance tools until a human rights-compliant safeguards regime is in place.»

Issues with post factum persecution

Previously, the main risk for protest participants was the possibility of detention directly at an event. The use of cameras and facial recognition systems makes persecution less predictable and carries additional risks.

Post factum persecution involves a serious invasion of privacy and influence on other areas of life not related to civic activism. Police officers can come both to the official and actual place of residence. In at least two cases known to OVD-Info, the police violated the inviolability of the home: in one, pushing away the mother of a participant of the protest event, they went to his room; in the other, they entered a student’s room in the dormitory.

Police visits to places of study or work have a marginalizing effect for a protest participant: there is a risk that fellow students or colleagues will treat him worse, he may be expelled or fired.

Public detention of a person in his usual environment, surrounded by colleagues, neighbors, classmates or university peers can lead to discrimination even if the police and algorithms are wrong.

At the same time, such detention is not an exceptional measure and does not meet the requirements of the Code of Administrative Offences — why can’t a suspect in an administrative offense be summoned to the police station in accordance with the procedure established by law?

- For example, Leonid Gozman was detained five days after the protest on April 21 at the police station, where he was summoned by a district police officer in connection with his appeal to the Investigative Committee. At the station, he was shown a video from April 21, where it is clear that he is walking along Tverskaya Street, and a report was issued on the violation of the rules for participation in a public event (Part 5 of Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences). He was kept at the station until late in the evening. The court rconsidered the case a month later and imposed a fine.

Sometimes arrest is immediately enforced to post factum detainees. This practice contradicts the position of the ECHR, which draws attention to the need to delay the execution of arrest in cases of administrative offenses until the appeal hearing. In cases where a person is detained post factum, the need for immediate execution of the arrest seems even less justified than in the case of arrests at rallies.

Unlike most administrative articles, the statue of limitation under the most common «rally» article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences is not three months, but one year. That is, within a year after an event, report can be issued against its participants and they can be punished. If earlier such risks arose only for those detained at the rally, now any of the participants may face them. As a result, the protest participants are left waiting for a possible detention for a long time.

If there are three court decisions on administrative responsibility in connection with a rally entering into force within six months (under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences), then after the next protest a person may face a criminal case under the so-called «Dadin article» (Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code). To initiate a case, it is important not when the events took place, but when the court decisions came into force. Post factum liability gives law enforcement agencies the opportunity to manipulate these deadlines, bringing the dates of resolutions closer, even if the events themselves did not initially fit into six months. This increases personal risks for the protesters, and in combination with the complex wording of Article 212.1 of the Criminal Code also intimidates them.

Artem Pugachev, who was taken to the police station directly from his dorm room, had already been held liable for participating in the event on February 2. Although this was only the second report for him under Article 20.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences, the post factum detention forced him to reconsider his attitude to participating in protests:

«I don’t want to get caught [again], you can get Article 212.1. To be honest, I see the opportunity to participate for myself now only in the form of some kind of moral or financial support, but not personally. At least in the near future, until all these cases «burn out».”

In practice, not all protesters face post factum persecution: apparently, only some individuals can be identified so far. In addition, it can be difficult to prove in the courts that a person really participated in the protest if they were not immediately detained. Nevertheless, the very presence of the threat of persecution and the listed negative effects has a high potential to demoralize civil society and becomes a lever for further restriction of freedom of assembly.

Conclusion

The year 2021 was marked by post factum detentions of protesters on a large scale. In Moscow, such detentions began in January and by autumn had become common practice.

For example, participants of a meeting with the Communist Party deputies on Pushkin Square on September 20 were subjected to mass detentions in the subway and on the street. Four days after the event, the Moscow Ministry of Internal Affairs issued a statement informing that more than 30 people were detained in connection with it and «a set of activities aimed at identifying the participants continues.»

Post factum persecution is associated with additional negative effects: an extended sense of threat, the risk that police officers will visit relatives or unexpectedly come to places of work, study, or home.

An increase in the scale of such detentions becomes possible with the introduction of street surveillance cameras in combination with facial recognition technology.

Despite the obvious threat to the privacy of citizens, in recent years, facial recognition systems have been actively introduced into daily use. In the banking sector, identification with their help is already offered, and you can enter the offices of some companies using biometric data. In addition, since October 15, it is already possible to pay for travel at all stations of the Moscow metro using the FacePay facial recognition system. Launching FacePay, Mayor Sergei Sobyanin said:

«We thought no one would sign up. Who wants to take pictures of themselves, enter their data into the system, link a bank account — it’s crazy. Fifteen thousand signed up in a few weeks. From September 15, we will double the number of stations, and from October 15, we will do it at all stations of the Moscow metro.»

Since July 2020, an «experimental legal regime» has been operating in Moscow, allowing companies engaged in developments in the field of artificial intelligence and included in a register specially created for this purpose to gain access to depersonalized personal data. This mode was introduced as part of the «National Artificial Intelligence Strategy for the Period up to 2030». Facial recognition systems also work on the basis of artificial intelligence. As explained on the strategy portal, this regime operates in order to «eliminate legal barriers» and accelerate the development and implementation of technologies in Moscow. The text clarifies that in the future similar «sandboxes» for the development of technologies may appear in other regions.

They are developing and implementing facial recognition systems and law enforcement units. In fact, in 2020, the Kommersant newspaper wrote thatby the end of 2022, the Ministry of Internal Affairs would spend 245 million rubles to develop the IBD-F 2.0 database for automating the work of police officers. It is planned to include in the IBD-F the subsystem «Identification. Biometric identification», which allows to search for people by images through a biometric facial recognition processor.

With the proliferation of facial recognition systems in everyday life, the number of sources from which law enforcement agencies can obtain images for comparisons with alleged protest participants, and the possibility of legal violations, for example, in the event of a data leak, is also increasing.

In the context of street protests, face recognition appears not only in the capital. Our research shows that the geography of technology is expanding. We managed to find clear indications of its use in court rulings issued against demonstrators in Nizhny Novgorod and Sochi. According to our data, after the protests on April 21, at least in 17 cities, people faced post factum persecution and the use of photo and video evidence — such a combination is likely to indicate the use of facial recognition.

The analysis of the scale of this phenomenon is complicated by the fact that the authorities, apparently, prefer not to document cases of the use of the technology. In the materials of cases of administrative offenses and in court decisions, we often find only indirect confirmation without direct indication. This also becomes an obstacle to judicial appeal.